The ‘How’ and ‘Why’ of Parse.ly’s Fully Distributed Team

My fascination with fully distributed teams dates back to year 2000. Back then, I was actively following the Linux and Debian projects, which were two of the most successful open source projects of that time. I used Debian on all of my systems and was amazed with the collaboration model they had engendered using tools like IRC (real-time chat) and Bugzilla (one of the original web-based bug management systems).

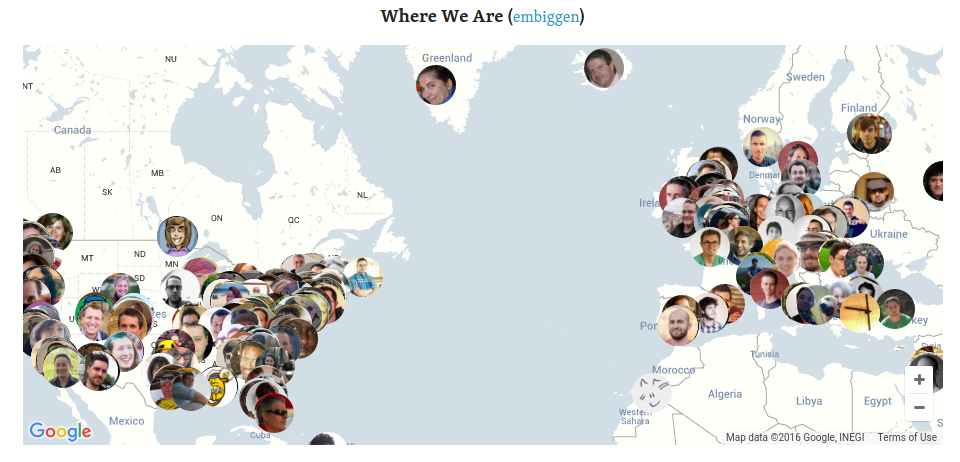

When I attended New York University, I used to give presentations to fellow computer science majors and students about the impact that free software was having on the larger technology community — large companies, startups, academia, and management. One of my favorite images from that era was of Debian’s developer community, still available here. It shows very visually how great software can be written by motivated individuals spread across the globe.

Distributed Work at Morgan Stanley

When I began my career as a software engineer at Morgan Stanley, I found myself on a distributed team by accident. It included groups of developers in Midtown Manhattan, Brooklyn, Montreal, and India. Originally, the team was split between Brooklyn and Montreal, but over time it grew across four Morgan Stanley offices and also included employees who worked from home frequently.

At Morgan Stanley, our team didn’t realize it was fully distributed until very late in the project. We lacked the terminology for the kind of team we were — in fact, I only came to realize the true terminology recently in my blog post on the subject. Using my own terminology as a guide, I would say my team at Morgan Stanley was horizontally scaled across several offices, and that this eventually matured into a fully distributed team over the course of a couple of years.

Our confusion was not helped by the fact that in the beginning of the project, the technologists who were based in Montreal were actually consultants, not employees, of the firm. This led to some de facto hierarchy — I remember feeling as though the “core” team was in New York, while the “auxiliary” team was in Montreal. This was reinforced by the management who would regularly hold in-person meetings with members in the NYC office to make design decisions that had ramifications across the team, a classic example of what I would later come to call “out-of-band communication,” one of the anti-patterns of fully distributed teams.

By 2009, however, the team had found a groove and had established itself pretty firmly as a fully distributed team. We communicated primarily over an internal real-time chat system not unlike IRC. We held team meetings via phone conference and screenshare and did product design and brainstorming work via web-based tools. And any team member could work from home or from their office at their leisure. Our team wiki was active and brewing with design ideas, specifications, and roadmap planning.

One of the things I learned in my time at Morgan Stanley was the importance of focus, concentration, and “flow” for developer productivity. My manager gave me a copy of the dense book, “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience,” when he started to notice I had an interest in team culture and engineering management. My manager had a really interesting background — he was a self-taught hacker who spent his early adult life as the drummer for an experimental, instrumental punk band. Later, he shifted his interests to computer programming. But he drew a very important connection between the two activities: that they both put him into a “flow” state. And so, when he became an engineering manager, he drew analogies from his days as a band member for how to focus and harness the engineering talents of a programming team. We realized over the course of managing our teams that the fact that we operated in a distributed manner allowed us to optimize for “flow.”

When I started my own company in 2009, I wasn’t sure yet whether we’d be a distributed team, but I knew I wanted to preserve those positive aspects of the asynchronous communication culture that fully distributed teams tend to facilitate.

Face-to-Face

The biggest thing missing from fully distributed teams is true face-to-face communication. There are a lot of subjective qualities to this kind of communication — such as body language — that cause the brain to react slightly differently than other forms, such as written or even video conference. Having a face-to-face “kick-off” meeting among team members is critical to make the distributed team work smoothly. Not only does this humanize the relationships between team members in a way that audio/video simply doesn’t (seemingly for a lack of verisimilitude), but it also encourages some friendship and bonding relationships to form that are a bit tougher to facilitate via pure digital tools.

At Parse.ly, we have held several team retreats since our founding. We cook together, drink together, play poker, and hold competitions. We also have intense brainstorming sessions and even do a little free-form programming and hacking with one another. I call it a “workcation” because though everyone is working, everyone is also very relaxed and we try to pick backdrop environments that are vacation-like.

The retreats also engender a sense of empathy among team members. For example, they learn each other’s favorite sports teams, discuss books they’ve read recently, or share favorite productivity tips. These are details that come up more rarely in our “virtual office” because of the lack of idle moments — elevator rides, walks to lunch, etc. — that tend to occupy this role in co-located teams.

Body language is an important part of communication, but perhaps not as important as distributed team detractors make it out to be. This is perhaps one of the most common criticisms I hear lunged at fully distributed teams — that without body language, your communication channels will inevitably fail; that you need constant body language to understand and communicate with someone. Distributed teams do need to learn another individual’s personality type. Once that is accomplished, their brain will be very good at filling in their body language in future communication.

Focus and Communication

Parse.ly engineers report that the biggest benefit of the fully distributed team is being able to really focus on one’s work, and thus produce great things. Almost everyone on our team used to work in an office environment where it was not uncommon to be interrupted throughout the day by the people sitting next to you. Many of my colleagues recall times they would wake up early or stay at the office late just so that they could experience the serenity of a few hours of focused programming without the incessant cacophony of idle conversation caused by their peers.

We also have become more efficient about communication than the typical non-distributed team. Because we use so many digital tools for capturing discussions, requirements, development progress, artifacts, etc., we have learned to be smart about inter-linking these digital artifacts together and automating systems.

One example is how we handle customer support. Whenever a customer has an issue with one of our products, this is captured in a web-based support tool. Our support team can chat with the customer and then link the customer issue to a ticket in our bug tracker on Github. The support staff can optionally notify an engineer for confirmation via our real-time chat system, Flowdock. Once our engineer closes the ticket and the fix is pushed to production, the customer is notified via the support tool. We have closed hundreds of tickets without having any in-person meetings, “all-hands” planning sessions, or 1:1 phone calls. But what’s more, because of all of this activity is web-based, it is also tracked. That lets us create engagement dashboards for different customers, where we take number of opened and closed issues into account. Asynchronous communication channels tend to have these “cascading benefits” — the more fully digitized a process, the more prone it is to analysis and optimization. Of course, there are trade-offs, too — and that’s where a team has to apply its judgment.

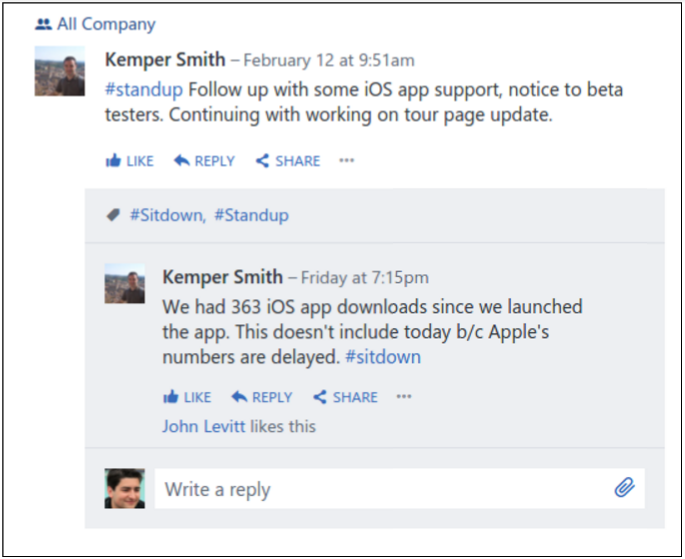

Another example is how we report progress to one another. We use the group messaging system Yammer to communicate short status updates on a daily basis. We have a team convention called “daily #standup’s and #sitdown’s.”

Every day, each employee begins by writing a message on the group messaging service Yammer, with “#standup.” In it, he or she outlines the tasks being worked on that day, and the goals by the end of the day. At the end of the day, they write a message preceded with “#sitdown” that reflects how they did at accomplishing their standup goals and what comes next.

Our team does this practice religiously, and it completely eliminates the need for “status update” meetings present in so many (in my opinion, dysfunctional) organizations. You can simply review the Yammer stream around 11am and you know exactly what everyone is working on. You can review it around 6-7pm (or the next day) and you know exactly where everyone ended up. No meetings necessary.

Just think of all the hours of time saved over the course of the lifetime of our organization. We’ve been using Yammer in this way for more than five years. I imagine, between the saved time from eliminated status update meetings and from our teams’ lack of a daily commute, our product organization has saved many man-months of time. Adding manpower won’t necessarily make a project more productive — but removing useless time-wasters certainly will!

Not Just Engineering

Remote work isn’t just useful for engineers. System administration and devops, for example, works perfectly well distributed. We also hired full-time designers who are fully distributed.

However, one area where the distributed setup falls short is enterprise sales. Our sales team is located in NYC. This is because they want to be close to our biggest customers, they want to be able to have regular in-person sales and support meetings, and because sales/support are inherently non-focused activities. The way to close a sales deal within a day isn’t to write code for 6 or 8 hours straight without interruptions. Instead, they need to hold three in-person meetings, write twenty emails, make ten phone calls, and attend an after-work cocktail hour or meetup.

I also think good sales/support teams are built around personal relationships — the energy created by a sales team is truly “physical,” similar to a well-tuned sports team. That is exactly the kind of thing at which a co-located setup excels. Finally, there are many media industry conferences in NYC and our sales team is able to take advantage of this to get new leads and keep the pipeline running.

That said, all of our sales/support staff — in true fully distributed team style — must use entirely digital tools for managing their work and productivity. They sit in the same chat system all day with the engineers, and communicate with them regularly. Above and beyond the tools used by the engineering team, they also use tools like Salesforce, Marketo, GDocs, Dropbox, and Trello, which have become standard cloud productivity tools anyway.

The distributed nature of our team engenders smooth collaboration between the two “departments” (if you can even call them that). I also think that because digital tools are the primary way we collaborate, it allows us to take a more methodical approach to our support and sales process.

The Future

Fully distributed teams are only going to get better — and more common — over time. Our tools are simply getting great at this stuff.

For example, Google Hangouts (http://hangouts.google.com) offers group video conferencing for large teams for free. We use Google Hangouts at Parse.ly to hold full team meetings. So, face time is now distributed, too, and multi-computer collaboration is getting easier even in synchronous modes.

I also recently discovered a tool called Rabb.it (http://rabb.it) which allows you to watch streaming movies and conference talks together over the web. It’s a really fun experience and shows a path toward how more camaraderie building activities could happen over the web.

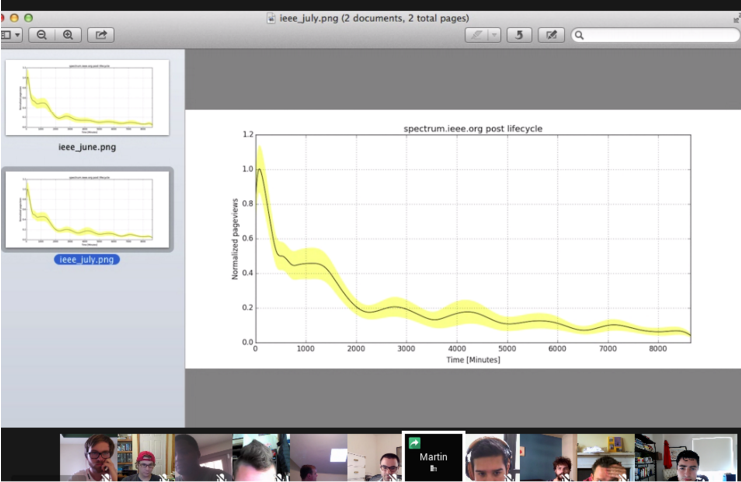

I also think some technology will enable collaboration methods that were simply deemed impractical in the age before distributed teams.

For example, one of my friends who is a VP of Engineering at another startup records screencasts using Screenflow, a Mac OS X screen recording software package. Rather than writing a wiki page on how to set up a developer’s environment, he created a screencast that walks the developer through it. This was so successful at onboarding new employees onto his team, that he started doing it for more and more things. He’s created a kind of “Khan Academy” for his internal documentation, where new hires can learn at their own pace.

Learning from his example, I’ve recorded a three-day Python training course called “Python for Data Analytics.” It was cheap and easy to record: Google Hangouts on Air for the raw video/screensharing, and then a couple hours in Final Cut Pro to edit the results and re-upload to a private YouTube channel. But now, rather than spending three days training every new Python engineer on the team, I just send them a link.

So, technology — and, in particular, audio/video technology — will help distributed teams along in the next 10 years. We’re moving away from one-on-one conversation as the primary way to collaborate and toward many-to-many.

I also think that the world has not fully internalized the degree to which technology systems impact collaboration approaches. For example, I don’t think Github is “simply” a code hosting system. It is actually a social experiment that fundamentally changed the way software engineers — in open source projects and in their own company projects — collaborate with one another. Many other experiments like this are happening right now with the new breed of project management, code management, and team collaboration tools. I’m quite excited about the future.

Fully distributed teams are now not only viable, but in many ways superior to co-located teams, especially for software engineering work. I suspect that will continue.

Finally, as someone who has read Frederick Brooks (author of “The Mythical Man-Month“), I find it very exciting to think that fully distributed teams may actually provide a way to soften the impact of Brooks’ law. Brooks stated that “adding more manpower to a late software project makes it later.” Fully distributed teams attack the two pillars of Brooks’ arguments: ramp-up time and communication overhead.

I would consider it a great achievement indeed if this field’s progress shows that not only can fully distributed teams be as productive as co-located ones, but also that they can be more productive at scale in spite of Brooks’ law.

Want to defeat Brooks’ law with us? Parse.ly’s team is fully distributed, and we’re hiring. We can hire people who live almost anywhere. Get in touch.