Platforms and Publishers: Is the Glass Half Empty?

The tone of a new report released by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism,” is striking.

The report, which outlines the effects of third-party distribution on news publishers, is at times dark (“Many in the room likely felt empathy with the watermelon, as their businesses were being squeezed slowly to the point of implosion by external forces beyond their control.”) and urgent (“In the wake of the election, we have an immediate opportunity to turn the attention focused on tech power and journalism into action.”).

The cumulative findings seem to stack up against publishers’ best interests, highlighting how platforms have encroached on core activities of publishers, the proliferation of fake news, and the influence of social platforms on editorial content. How optimistic should publishers be about the results of a convergence between journalism and platforms?

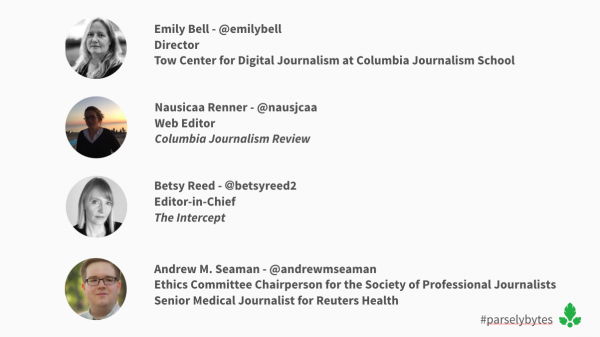

We had a chance to hear more about the topic at a recent panel discussion between speakers from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism (including Emily Bell, one of the authors of the report), The Intercept, and the Society of Professional Journalists.

Consequences of Platforms Behaving Like Publishers

Social platforms have had concrete effects on newsrooms. Betsy Reed, editor-in-chief of The Intercept, explained, “Social media is not only where we distribute our journalism; it’s where we do our journalism.”

Platforms have impacted how journalists frame and source stories. Nausicaa Renner, web editor at the Columbia Journalism Review, underscores how social platforms influence the way newsrooms allocate resources, especially in response to the development of new tools and platform features. In a fundamental way, according to the Tow Center report, “The influence of social platforms shapes the journalism itself.”

“Publishers are making micro-adjustments on every story to achieve a better fit or better performance on each social outlet. This inevitably changes the presentation and tone of the journalism itself.” —”The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism”

Betsy Reed said, “We very much think about social media when we’re framing a piece.” She has found “the kind of content that tends to be shareable and travels is on the simpler side,” though “high emotional content” that is “very complex, and erudite, and deeply argued, and informed…travels like crazy on social networks.” Adapting the way a piece is framed to optimize its success on social platforms isn’t necessarily detrimental to the writing process:

“We’ll try to take an argumentative tone. We’ll try to connect emotionally with an audience with the framing of a story and I don’t think that that’s necessarily a bad thing for journalism.” —Betsy Reed, editor-in-chief of The Intercept

A section header in the Tow Center report refers to “The Publishers’ Dilemma.” On the one hand, relying on platforms for distribution means publishers face a lack of transparency, unreliable metrics, and the changeability of algorithms and other features. But without third-party distribution, publishers relinquish an opportunity to connect with and grow their audience.

What can publishers do when confronted with this catch-22? Going forward, the panelists highlighted the importance of urging transparency and varying business models.

Increased Transparency from Third-Party Platforms

Currently, a lack of transparency from platforms is contributing to the friction with publishers. The Tow Center report called out the “single most controversial, influential, and secretive algorithm in the world is the one that drives the Facebook News Feed.”

Are the steps being taken towards transparency going in the right direction? Andrew M. Seaman, senior medical journalist for Reuters and ethics committee chairperson for the Society of Professional Journalists, thinks it’s a good sign that Facebook wants to help, but there has to be more of a dialogue. If the platform moves forward without collaborating with news publishers, the result will be “Facebook’s idea of a solution and not probably what’s best for journalism and the public.”

Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, had a more optimistic view. She reiterated that Facebook “has shifted a long way in just three or four months.”

At this time, having an “engaged conversation” with platform companies—not just Facebook—is critical. “The founders of Facebook and Google are not monsters,” Emily said, and there’s an opportunity for a dialogue that will continue to encourage transparency and a role for platforms in protecting journalism.

Encouraging Direct Reader Support

Advertising works when scale is involved, and platforms drive scale. Publishers are gravitating away from focusing on scale towards focusing on loyalty and direct reader support.

Betsy Reed said, “One of the financial models that I think is most promising and potentially healthy for journalism involves direct reader support.” Subscription models and donations to nonprofit newsrooms help build a community around journalism.

Andrew Seaman agreed, saying, “One of the things that is sort of heartening to me is that if we move to a subscription model for content that is going to be delivered visually, we get better journalism.” From an ethics perspective, better quality journalism rises to the top in this model.

Andrew also stressed the work that needs to go into affecting progress: “We need to do groundwork to actually improve media literacy and rebuild trust in journalism.”