Outsized influence: the size of social media platforms has little to do with their referral traffic

I often wonder if the allure of a social platform is worth the hype. My interests as an analyst and content strategist sometimes feel at odds with my interests as a user and consumer. The strategist in me wants to understand how trends in social media influence a business’s potential to grow. The user in me prefers a place to find like-minded individuals and relevant information. The point of tension arises around behavioral tracking: I want to trust that my personal information remains secure and in my control. There are benefits to tracking my online behavior (not only for the platform, for myself too), but I still want the option to take a step back if I feel like it.

My primary concern for other strategists out there—business analysts, social media gurus, audience development professionals, marketers—is whether the audience on a platform is even worth pursuing. If it is, then my secondary concern is how to measure success on those platforms.

I’ll always be partial to triangulating success based on user and platform intent. In other words, try to understand why people use each platform. Don’t try to game the algorithm. Indeed, what makes social media platforms unique from other sources is the appeal of not only advancing your message to millions or potentially billions of people, but users’ ability to share and advance it for you.

- When it comes to social media, is the pursuit of a new audience justified?

- Is the promise of reach an old habit that we just can’t kick?

- And have we overestimated, or perhaps underestimated, the role of all those shares, likes, and comments?

The promise of audience reach on these platforms is massive, and engagement data is an important signal of user interest. But at the end of the day, your main goal on these platforms is to make users interested in you. They may share your content, they may follow your handle, but the most explicit interest is measured through visits to your site.

Let’s dig into what the size of a social media platform and its users’ ability to share content can tell us about the type of audience that is referred to our network.

The promise of audience reach

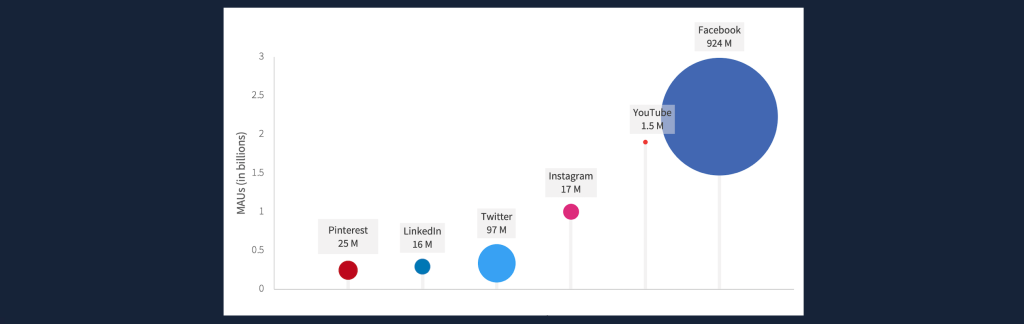

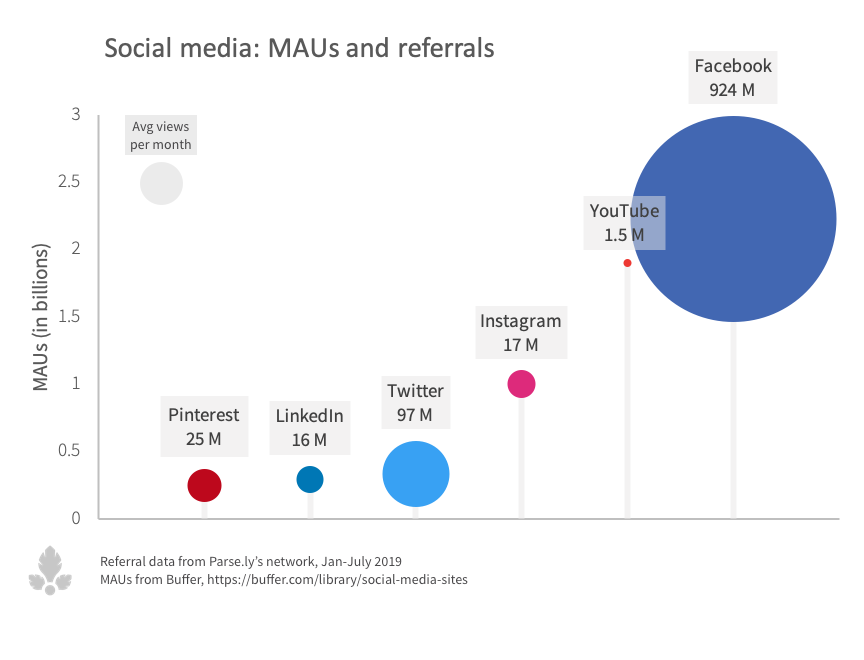

The success of a platform, in business terms, is often measured in active users. Let’s compare the size of each platform’s user base in monthly active users (MAUs) with the average monthly referral traffic it sent to Parse.ly’s network in 2019. This will give us a sense of scale in the measurable* social media market.

*By measurable, I mean identifiable. The opposite of this is unidentifiable social traffic, or dark social. I’ll get to that in a minute.

The height of each platform corresponds to the social platform’s MAUs, and the size of the bubble illustrates the amount of traffic the platform sends.

Facebook undoubtedly has the lion’s share: 2.23 billion MAUs drive nearly 1 billion views a month. The promise of audience reach on Facebook is palpable and considering the return on investment, maybe even reasonable. The hangover we feel from Facebook-first marketing is far from over.

The only platform that comes close to Facebook’s size is YouTube, with 1.9 billion MAUs. (Can barely see it, right? That’s how little traffic actually comes from YouTube.)

Instagram is next, and its 1 billion MAUs send a fraction of traffic to our network. One thing to note, we’ve seen an increase in the adoption of add-on link-in-bio products. These products, collectively, add 15% more traffic to our network on a good day, but individual sites might see 1-3x more traffic from these tools than they would from instagram.com alone.

Twitter has a third of Instagram’s users, but sends 6x the traffic.

How social interactions factor into referrals

Social interactions—shares, likes, retweets, follows, all signals of interest—are a common way to triangulate success on a platform. They signify a type of “buzz,” and can be a proxy for brand awareness. Therefore, it’s important to understand how these features are (or aren’t) supported in each product.

Many strategists aren’t ready to give up on the influencer market. According to Buffer’s 2019 State of Social report, 37% of marketers have invested in influencer marketing, and most of them will continue to do so.

Instagram, perhaps the most notorious platform for influencer marketing, might have that kind of allure because of the sheer size of its user base. But the product itself limits the user’s ability to share content, except for iterations on Instagram Stories and through private messaging.

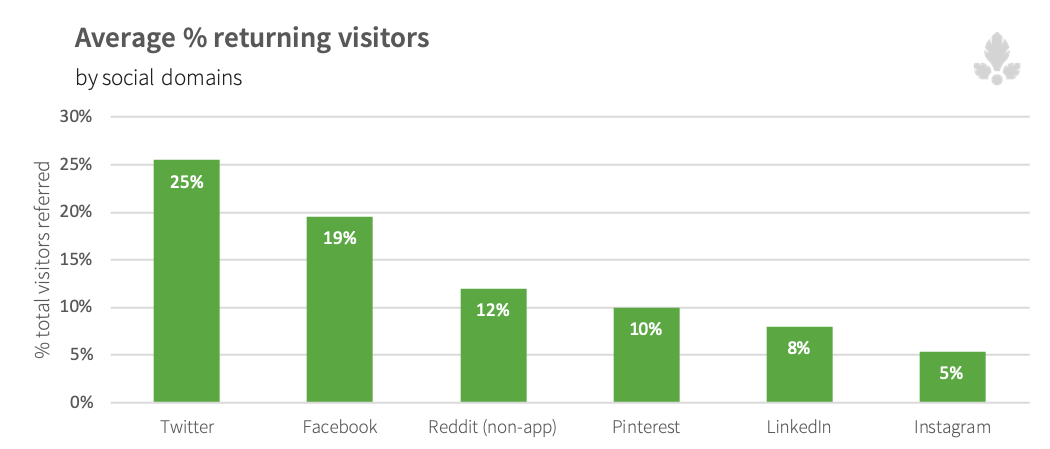

With all of these factors combined, what little traffic Instagram generates is likely to be from a brand new audience: only 5% of visitors from Instagram have been to the same site in the same month.

Twitter, on the other hand, is built on the very notion that its users should share ideas and information freely.

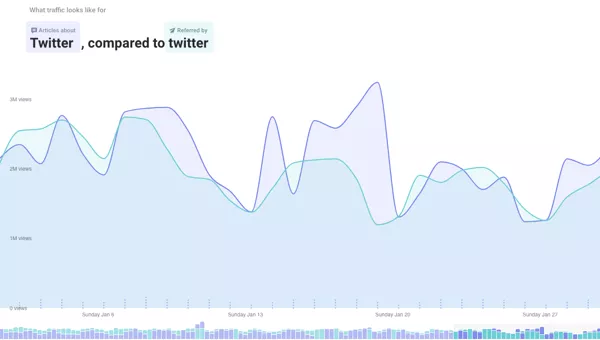

Pound for pound, Twitter sends more traffic per user than Instagram, and its influence actually extends off of the platform itself. At times, there are more views to articles about Twitter than views from people who find articles and stories on Twitter.

Twitter is used in media, entertainment, and political circles to capture citizen sentiment, but according to Pew Research, most tweets represent a small minority: 80% of tweets are sent by only the top 10% of Twitter’s users. These users are, in a way, Twitter’s influencer market.

And that outsized influence is substantial: one in four visitors from Twitter is likely to have visited the same site at least once before in the same month.

How social interactions factor into product development

Patterns in social interactions are interesting to me not only in aggregating the “buzz” or awareness on a platform. In recent years, these metrics are increasingly at the heart of social media product development.

The way in which users share content with one another was central to Facebook’s product changes in 2017-2018. Instagram facilitates user connections but limits those interactions to images or hashtagged themes. The platform simply does not support hyperlinking within a post, and at this point, that is unlikely to change. Twitter’s stickiest feature is its ability to amplify user voices, a point underscored by articles that mention Twitter itself.

Social interactions reinforce what the social media product has promised to sell: its users.

So it’s important that we don’t forget the reason social interactions even exist on these platforms. Social platforms are developed to study user behavior in a way that curates and amplifies users’ interests within their social network. Stronger network signals imply smaller audience segments: personas which can be summarized and commodified.

No matter how you slice it—by shares, likes, retweets, or comments—all social interactions reinforce what the social media product has promised to sell: its users.

A return on investment

This might make you wonder, for all the social engagement data out there, what’s really in it for you? There will always be content that resonates with specific audiences and not others. That’s a given. But there’s a need to see real results.

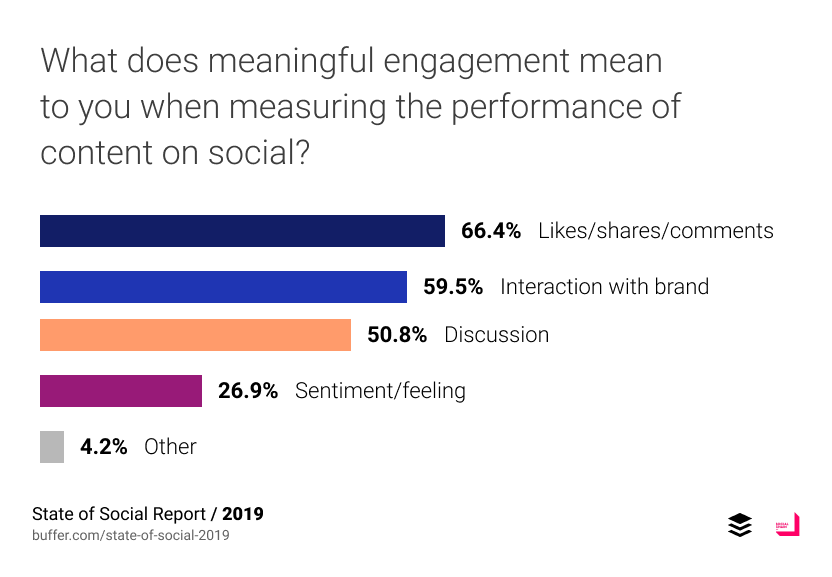

Buffer’s report indicated that marketers gauge success by interactions with content and interactions with the brand. In other words, all those cursory likes better turn into something that benefits the brand directly.

And platforms recognize this.

Product developments that facilitate in-app purchases and rumors of hiding the “like” count on images may indicate Instagram’s focus on creating meaningful interactions. LinkedIn shut off its shares API a while ago, and Pinterest might be a search platform in social clothing. But that data isn’t gone. The way in which users interact with one another is the product’s most valuable asset.

After all, curating more valuable audience segments means better audience targeting and points of conversion. This is precisely what social media offers to businesses like yours: meaningful interactions with your brand.

Let’s not forget who ultimately dictates what makes an interaction meaningful: the users themselves.

Marketers aren’t pursuing dark social apps. (And that’s okay.)

But there’s an elephant in the room and that’s social interactions and traffic that we can’t measure, or dark social. The popularity of dark social platforms indicates that users might be growing tired of the lack of meaningful interactions on other social platforms.

For this experiment, we split dark social out from its umbrella category, “direct” referrals. All direct referrals have null sources. A user might be likely to type in a homepage url, and come to the page directly, so views to non-post pages would remain a direct referral. But if the user landed on a post, we might assume they had to come from somewhere. The assumption we’re making is that users are unable and unlikely to type in an entire url manually, but are finding this content through messaging apps, email, or other unknown sources.

It’s impossible to say how much traffic comes from each platform, but collectively, they drive more traffic than Facebook and for the dozen or so platforms we studied, serve over 8 billion users.

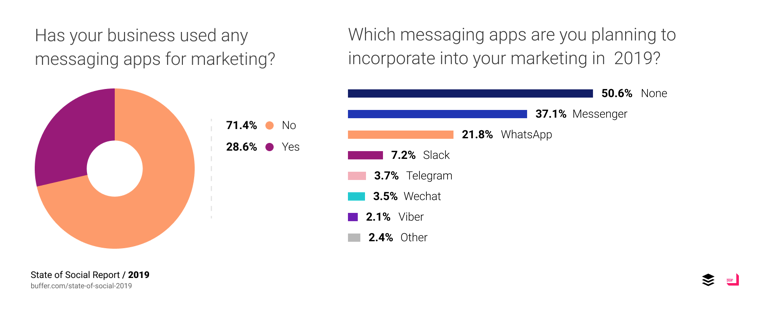

Despite the popularity of these platforms, according to Buffer’s survey, 71% of participants had not used these apps to promote their content. And half don’t plan to.

Users need space

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerburg has described Facebook as a digital town square, an apt metaphor for most social platforms. Surrounding and supporting the town square are myriad shops, a civic center, maybe a courthouse. Social platforms know that the end goal is getting users through the doors of these places. And they know it takes some barking to get them there.

If measurable social platforms are the town square, then messaging, email, and other dark referral traffic is a retreat into privacy. It’s the corner pub, it’s your friend’s living room.

Alexis Madrigal coined the term back in 2012. Madrigal’s description is poetic and truer now more than ever: “There’s no way to game email or peoples’ instant messages. There’s no power users you can contact. There’s no algorithms to understand.”

The way messaging and email platforms are built, the very infrastructure in which users share information, reflects a growing mistrust of, or at least exhaustion with platforms and advertising.

Dark social platforms are a web citizen’s revolt against the commoditization of their identities and interests.

It may sound dramatic, but dark social platforms are a web citizen’s revolt against the commoditization of their identities and interests by even the most trustworthy media outlets and beloved brands.

Rebuilding Trust

And that’s really what’s at the core of dark social: trust. Rather than “despite” their rising popularity, it’s because of these apps that newsletters, Slack, or WhatsApp groups have enjoyed small, but remarkable success. As far as users are concerned, no one commoditized their interests with or without their consent—they willingly opted in. They clicked a button that said, literally, “sign me up.”

The latest product developments on measurable social platforms signal a much larger trend: no matter how much you love the vibrancy of the town square, sometimes, you just need some privacy.

Major social platforms have opted to remove or obscure social signaling, but I can’t help but wonder if it’s because they’ve taken a page out of the dark social handbook to provide a bit of peace of mind for the user. No doubt these users’ interests are still aggregated, but if it doesn’t feel like they’re constantly being watched and that every one of their likes is being tallied before them, then perhaps users will interact in ways that are more individualized and driven by their own intuition.

Unlike those interviewed in the Buffer study, I don’t expect messaging apps to realize their full potential this year. In fact, I expect this trend to remain as vague as the users who generate it. If anything, the latest product developments on measurable social platforms signal a much larger trend: no matter how much you love the vibrancy of the town square, sometimes, you just need some privacy.